This is one of several pages that contain our research notes about the Holy Lance of Love. This is part of the Glass Bead Game experience. You will not find our research in one, nice tidy place because the story is about your own awakening consciousness. You need to work through the material yourself to discover your own truth about the Mystery of Golgotha.

This is one of several pages that contain our research notes about the Holy Lance of Love. This is part of the Glass Bead Game experience. You will not find our research in one, nice tidy place because the story is about your own awakening consciousness. You need to work through the material yourself to discover your own truth about the Mystery of Golgotha.

To get started on this digital “Indiana Jones” story, click on the headline link below, where you will can follow along chapter by chapter, eventually being linked to this page where the material will make sense to you.

Enjoy the cyber expedition.

Searching the Destiny of the Holy Lance of Love

.

.

Research notes:

https://books.google.com/books?id=HfhyBgAAQBAJ&q=alfonso+jordan#v=snippet&q=alfonso%20jordan&f=false

Alfonso & Conrad III

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conrad_III_of_Germany

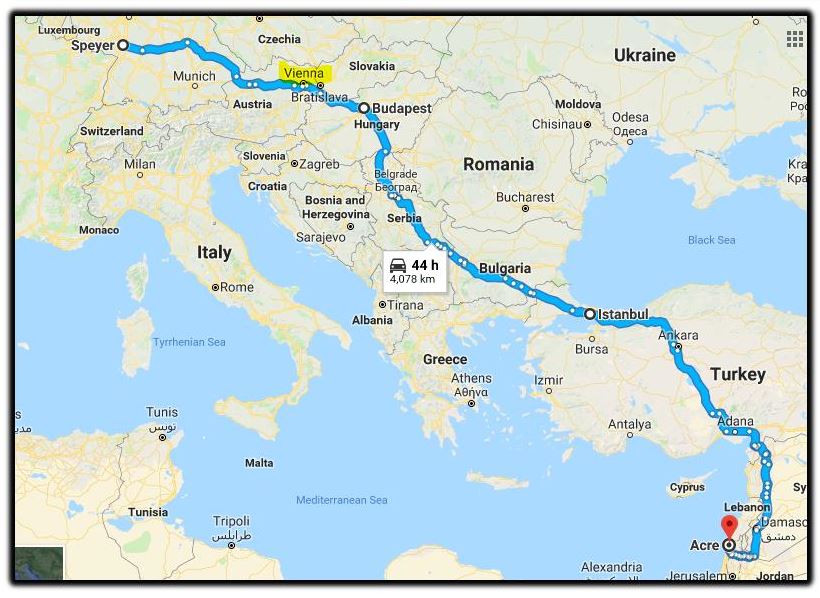

Alfonso and Conrad III battled and travelled together until Caesarea, where Alfonso was likely poisoned. It could be here that he bequeathed the Holy Lance into Conrad III’s care, who did travel back home to Germany via ….. Vienna, where he could have deposited his relics into the hands of Knights Templar for later claiming by Alfonso’s family. He was in a hurry because King Louis VII was attempting to usurp his alliances. One thing is for sure, he would have consecrated a holy copy of the Holy Lance to ensure his good fortune… hence the copies in legend. Maybe not so much legend as understandable next steps.

Notice how Conrad III’s reign touches Nuremburg, Poland, precursor to Hapsburg and Constnatinople where Raymond Saint-Gilles’ chronicler’s Anna Comnena’s uncle is on the throne. Anna is the person who wrote:

“Alexius [the Emperor, Anna’s father] had a deep affection for [Raymond of] St Gilles because of the count’s superior intellect, his untarnished reputation and the purity of his life. He knew moreover how greatly St Gilles valued the truth, which he valued above all else, whatever the circumstances. In fact, he outshone all Latins in every quality, as the sun outshines the stars.”[i] [ii]

Could this have been the source of the Holy Grail myths AND Germanic/Polish/Spear of Destiny legends?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Council_of_Acre

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/cdesource.asp

https://gw.geneanet.org/comrade28?lang=en&n=toulouse&oc=0&p=count+alfonso+jordan+of

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_II,_Count_of_Tripoli

However, Raymond was descended from Saint-Gilles through Bertrand of Toulouse, a son with disputed legitimacy.[25] Saint-Gilles’ legitimate son, Alfonso-Jordan, was born after Saint-Gilles started to use the title of count of Tripoli, making him his father’s lawful heir in accordance with the idea of porphyrogeniture.[26]

Porphyrogeniture, also sometimes referred to as born to the purple, is a system of political succession that favors the rights of sons born after their father has become king or emperor, over older siblings born before their father’s ascent to the throne.

Alfonso-Jordan was one of the supreme commanders of the Second Crusade, but he died shortly after he landed at the Holy Land in April 1148.[26][27] Because of his unexpected death, gossip about his murder started spreading among the Crusaders,[28] although he most probably died of natural causes, as a consequence of his lengthy voyage across the Mediterranean Sea.[29][30]

An anonymous Syrian chronicler accused Raymond of the crime, stating that he poisoned Alfonso-Jordan because he feared that his uncle had come to seize Tripoli.[26] Lewis emphasizes, the chronicle “is hardly the most reliable piece of evidence, so some skepticism about Raymond’s involvement in Alfonso’s death is surely advisible”.[26] An other contemporaneous author—the continuator of Sigebert of Gembloux’s chronicle—was convinced that Raymond’s sister-in-law, Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem, had poisoned Alfonso-Jordan, because she wanted to prevent him from claiming Tripoli.[31]

Raymond did not attend the assembly of the leaders of the crusade at Acre on 24 June 1148.[30] He also kept away from the crusaders’ campaign against Damascus.[30] In contrast with Raymond, Alfons-Jordan’s illegitimate son, Bertrand, who had arrived in his father’s retinue, participated in the Crusaders’ fights.[32] He decided to lay claim to Tripoli and took possession of the fortress of Araima in the summer of 1149.[33][29] After being unable to expel Bertrand from the fort which controlled important roads in the county, Raymond sought assistance from Mu’in ad-Din Unur, the Muslim ruler of Damascus, as well as from Zengi’s son, Nur ad-Din.[34][35]

The two Muslim rulers captured Araima and imprisoned Bertrand and his family.[35] After destroying the castle, they returned the territory to Raymond.[36] Raymond granted the land to the Knights Templar in the early 1150s.[37]

Most likely Alfonso, realizing he was poisoned, would have hastily bequeathed the Holy Lance to someone trusted near his side, like Conrad III, another crusading general?

Could Conrad III’s temporary stewardship of the Holy Lance from mid-April 1148 until DATE when he passed through Vienna when he deposited it at the Knights Templar (most likely to be retrieved by his heir) be the source of the Germanic Holy Lance legends?

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Conrad-III

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuel_I_Komnenos

https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy/The-age-of-the-Hohenstaufen#ref318310

The age of the Hohenstaufen (Conrad III being the first)

During the 12th century a new political order developed in Italy. It was not a tidy process, however. In the south the ascendancy established by the Normans of Capua and by the Hautevilles gained strength with the conquest of Sicily from the Muslims in the late 11th century. Following the death of Robert Guiscard, his brother, Roger I, count of Sicily, went to the mainland to consolidate his position.

His son, Roger II, succeeded in establishing a Norman kingdom. Recognition for it, however, was slow in coming. Roger first obtained it from the antipope Anacletus II (1130–38) and then, under conditions that revealed the weakness of the papacy before Norman power, from Pope Innocent II (1130–43) in 1139. The papacy continued to seek support from the French monarchy in order to offset growing Norman influence.

On the other hand, victory in the Investiture Controversy, even though compromised, created a situation that enabled the 12th-century papacy to assume leadership of the reform movement throughout Europe. The Lateran Councils of 1123, 1139, and 1179 marked important stages in the development of the reform papacy.

From Urban II on, the central administration of the church expanded. By the mid-12th century—about the time that the monk Gratian was compiling his Decretum, the most important collection of ecclesiastical law up to that time—Rome’s position as a court of appeals was growing faster than its judicial machinery could possibly accommodate.

The process of definition and extension of papal control over ecclesiastical matters inevitably led to conflict with secular rulers. The determination of the papacy to protect its independence and, after the death of Matilda of Canossa in 1115, to hold onto the vast inheritance she had bequeathed to the Roman church in central Italy, as well as the ties that united the papacy to the reform bishops and to many of the laity who had supported the reform in their cities, signaled changes that had taken place since the Concordat of Worms in 1122.

Finally, the keystone of the new order lay in the strength, as yet untested, of the communes. Vestiges of imperial support certainly remained both in the cities and in the countryside, but the old cause had given way before the real interests that were taking shape during this period.

The emperors of the Hohenstaufen dynasty that succeeded the Salian dynasty attempted to revive the imperial position in Italy. The first efforts of both pope and emperor in the period following the Concordat of Worms were, however, based upon the assumption that something of the old relationship remained.

In part, this attitude may have been encouraged by the slight attention that Lothar II (or III; 1125–37) and Conrad III (1138–52) paid to Italian affairs. Lothar’s efforts against the Normans were ineffectual, and he focused primarily on civil war in Germany. His rival and successor, Conrad III, the first Hohenstaufen king, devoted considerable energy to the Second Crusade, which had been promoted by the Cistercian monk and monastic reformer Bernard of Clairvaux.

The dominant role of Bernard of Clairvaux certainly influenced the selection of his former disciple, Eugenius III (1145–53), as pope. Forced to seek refuge in France by the political situation in Rome, where the radical reformer Arnold of Brescia stirred both feelings of independence and a demand for more-extreme reforms within the church, Eugenius cooperated with Bernard in the preaching of the Second Crusade.

Although the Crusade was conceived originally as an enterprise to be led by the Capetian monarch Louis VII (1137–80), Conrad III was included when it became clear that there would be large-scale German participation. The Crusade fell well short of expectations, and Conrad returned to Germany in 1149 to resume his imperial program. Eugenius, who faced Arnold and the rebellious Romans and who was heavily dependent on Roger II of Sicily during Conrad’s absence on Crusade, hoped that Conrad’s return would provide the means to reestablish papal control in Rome, but turmoil in Germany prevented the realization of his desire. Conrad died without being able to journey to Italy to receive imperial coronation. Eugenius died the following year.

Reblogged this on Blue Dragon Journal.